A friend approached me one evening, an older (but not ancient) woman, wanting to know if she correctly understood what she had heard—that I had at one time been a professional photographer in New York City.

Having no idea where she might have acquired such misinformation, I assured her that like most persons who own a digital camera I'm an enthusiastic taker of snapshots, but among the thousands, aside from a few cases when the subject, lighting, and the spasm of my trigger finger coincided serendipitously, there are no masterpieces among them; that my ignorance of the technicalities of photography approaches the profound; and that no one has ever paid me a nickel for taking a photograph, nor have I ever attempted or hoped to receive compensation for doing so. In short: No, I am not now, and never was a professional photographer in any sense of the word.

To keep the conversation rolling, and because I intuited to some degree what she may have heard inklings about, I added that my artistic career was limited to curtailed attempts to compose music, during part of which efforts I did indeed live in New York, but that was a very long time ago—the late sixties and early seventies. I added that it was not utter failure to be any good at it that brought that phase of my life to an end, but the need to remove myself from an unhealthy and destructive environment. Most people of my age and older are well aware or can imagine that the popular music scene in New York City in the sixties was eminently life threatening—physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually—to anyone who got caught up in the thinking and conduct of that mad era. Having no reasonable alternative that would allow me to stay in the business, I simply got out.

The friend, who seemingly understood what I said, then added the question: "Was Mozart around there at that time, too?"

Mozart? Working in New York in the sixties? She thought perhaps I might have known him? Briefly words failed me. Finally, I was able to choke out the reply: "No, my dear. Mozart died in 1791. He was a contemporary of George Washington and the other Founding Fathers of the United States. That was two hundred years before my time. I'm a contemporary of Bob Dylan, not Mozart." "Oh!" she replied, apparently unfazed by the time gaffe, probably unfamiliar with the name Bob Dylan, but disappointed to realize that I had not rubbed shoulders with the particular celebrity I had named.

I love this dear lady, who was only trying to be friendly, and attribute her parochial naïvety to a deliberately self-inflicted withdrawal from contact with worldly society to a degree and for reasons that seem appropriate to her. Still, I have to wonder how one's Weltanschauung can become so discombobulated that a person's recognition of essential historical figures is skewed by centuries. The episode constitutes yet another demonstration of how easily a fundamentally ignorant person, by a simple misstatement can lead others to think, "If you don't know that, what do you know?"

Lemme see ... did the apostle Paul ever appear before Bill Clinton? Maybe I'll check that out on Wikipedia.

Friday, December 25, 2009

Monday, December 14, 2009

Festivus 50K 2009

On Saturday, December 12, I ran the Festivus 50K for the second time. The race is an out and back, mostly on the Olentangy River bike path, starting at its northern extremity in Worthington, Ohio, through the streets of downtown Columbus, where there's currently a lot of construction and opportunities for persons unfamiliar with the course to get lost, and back onto the bike path for a little piece before reaching the turnaround. The part from north of The Ohio Statue University is the best part of the course. South of OSU—yuck.

Near the end of the North Coast 24-hour race in Cleveland last October I resolved that I would not enter another ultramarathon until I lose twenty-five pounds. Festivus was the exception I had in mind all along because: it's free, a no fee no tee event where you provide your own support and record and email your finishing time to the race director if you care to have it listed; it's run on the bike path where I train three Saturdays out of four; in contrast to the previous two Sunday races, it was even scheduled for a Saturday, my usual long run day; I try to do a marathon or longer long run or walk once a month, and needed one for December. With January and February staring me in the face, I don't know if the weather will permit me to get one in either month. So I did the race.

Last year I finished in last place by a whopping margin of three hours and seven minutes, partly because I walked the whole thing, as my last training run for Across the Years, where I walked for three days, and partly because I missed the turnaround point (the marker had been removed), so walked an extra mile or so. Otherwise I would have saved an hour to an hour and a half and been last by only an hour and a half.

Before every race I go through a period of thinking: "I don't really have to do this. It's gonna be long. It's gonna be hard. I don't have anything to prove to myself or anyone else. No one is forcing me to do this."

The feeling is strongest when I get out of bed on race morning and check the weather. It's early. It's dark. I'm not a morning runner, though I've always been cranked and ready to go by the start of any race I've ever been in. There's too much to think about, going umpteen times over my checklist. I hate taping and Bag Balming my feet, but know I'll regret it if I compromise on any part of my proven routine. It'll be cold out there. I'll be alone all day long—but that's never stopped me from doing a training run.

Happily, I've never DNSed any race. If I say I'll be there, I will be. By the time I was dressed and ready to leave, I was anxious to get started.

I left the house at 7:45 to make the start time, set for 8:30. True to the forecast, there was nary a cloud in the sky, nor would there be all day long. The prediction was for a high of 35, which is warmer than it had been earlier in the week, and turned out to be an underestimate. More good news. I can handle that temperature.

I turned on the car radio, tuned permanently to WOSU, the NPR station at The Ohio State University, which broadcasts mostly classical music when it's not airing the usual NPR news and information programs. Some music perfect for the day was on—a baroque trumpet concerto, the sound as sweet and bright as peppermint. Just as I was starting to get into it the sound cut off. Oops, I forgot—the radio in my 1994 Mercury Grand Marquis will play for two minutes or less, then cut off for the rest of the day. I don't know why, though it seems to be temperature related. The only likely solution is to replace the radio, which I'm unwilling to do, even though there are several years of life left on the car.

Whoop! Suddenly the radio came back on, which usually doesn't happen. By this time some other cheerful noise was playing. Being in a jovial mood, I began to whistle along. Oops, I forgot—the blower fan for the heater in my car doesn't work, so when I whistled, I suddenly found myself fogging the windows with whistle steam. Dang! While trying to wipe off the windows with a rag so I could see, the radio cut out again. A guy can't even manifest being in a good mood these days.

I arrived twenty minutes early and saw a dozen or so runners standing where the start would be. Aha! I thought—a crowd of early arrivers. Looks like there'll be a pretty good number. I fumbled with my gear and my camera inside the car before getting out, realized upon stepping out of the car that I'd need to take off my gloves to work the camera, said nuts with that, tossed the camera in the trunk, turned around, and all the runners were gone. They turned out to be some running club assembling for their Saturday morning workout. I looked around and didn't see anyone at first who might be doing Festivus. I did have the right date, time, and place, right? I did. Within a minute or two runners started crawling out of their cars, mingling and making preparations.

There were reportedly forty to forty-five runners at the start. Some said they wouldn't be going the whole distance. After two years of living here, I still don't know many runners in Columbus, but I did get to talk to a few people, including familiar ones.

Festivus is informal to the max. Race Director Dan Distelhorst hoped everyone looked at the route on the Web site, or at least just knew what it was, since he wasn't planning on describing it. One woman, possibly from a team of four people who drove in from Cincinatti and finished together, asked: If you've never seen the course is it possible to get fouled up? I was too quick to speak up and said it couldn't be easier. I hope she didn't get lost, because there are in fact some tricks it would help to know about, particularly getting through all the construction downtown, and also a couple of places on the bike path itself that could be confusing.

True to the forecast, it turned out to be gorgeous, with an official high of 41, and no wind to speak of—for one who was adequately dressed. I talked to one runner before the race who was worried he might be overdressed. He was standing there in shorts and a sweatshirt, while I stood by in running underliners, long johns and tights on the bottom, long john shirt, a North Face technical shirt, a hoodless sweatshirt, and my Across the Years 1000-mile jacket on top, a beanie and full head cover, and a pair of running gloves covered by down filled gloves. On my back was my 100-ounce Camelbak Mule, filled only halfway, which turned out to be a mistake. The other runner voiced the maxim: "Dress for the end of the race, not the beginning!" Fine. In my case by the time I got back to my car with no heater it would be pitch dark, or close to it, and cold again, so I was prepared.

Finally we took off. The official weather report said the low temperature was sixteen degrees Saturday, though it didn't seem quite that cold to me. But it was bright and windless, with prospects for a nice day. As we took off, I overheard one lady complain to another about being cold. The other replied: "It should get better in about twenty degrees."

By one hundred feet from the start I was in last place. The other runners were out of sight by two hundred yards, and I never saw any of them again until I encountered them as they were returning, which began just north of OSU, nine or ten miles from the start, when I still had many miles to the turnaround. Unlike last year, this time at least I recognized most people coming back, or they recognized and acknowledge me, as friendly greetings were exchanged. I had the good fortune to be seen running rather than walking on most of those occasions.

People have asked me what I think about when I run long distances. The answer could fill an entire essay. One thing that occupied my mind on this day was what I've most recently been reading: a book that discusses social changes in the United States in 1800, the year Thomas Jefferson was elected President and the whole nature of the government changed, with consequences that remain down to today.

As I got near to OSU, I saw many geese and a few ducks—hundreds of them—all in the water, and every single one absolutely motionless. Usually they're swimming around, at least slowly, bobbing for food, honking and quacking and doing all the geesely, duckly things that geese and ducks do. It was like a scene from Alfred Hitchcock's movie "The Birds." They were just there. Some had their heads tucked in, apparently sleeping or maybe just trying to keep warm. I guess I would turn motionless pretty quickly myself if I were sitting naked in the middle of a body of water that was near freezing. I'm living my third cold season in Ohio; this was a strange, eerie but peaceful scene of a type I've never seen before.

I always take a good look whenever I pass by the Mausoleum—errr, make that the enormous OSU football stadium. It's hard to imagine that venerable shrine ever being replaced. It's been in operation for 87 years and is ideally located. Where would they put a new one? Putting an updated building on the same spot would probably be perfect, but where would they play during the years a new one was being rebuilt?

Living near The Ohio State University is one of the things I like best about living in Columbus; knowing it would be was one of the drawing points for me. I have no formal connection to the school whatever, only an emotional one. While growing up our family lived less than a mile from another Big Ten university football stadium, Northwestern's Dyche Stadium. My father taught at Northwestern a number of years. Later I spent six years as a student at University of Illinois, and even though I left school as a sixties radical, I loved campus life. Even when I lived for seven months in Buffalo, I sensed a connection with SUNY, as one of my band's musicians played in a new music ensemble there, and I even played two concerts there myself. In Phoenix, we had Arizona State University, where my wife got both a bachelors and masters degree, and my daughter got her RN/BSN. Despite this, the nature of the city is such that I never felt any special attachment to or special interest in that school the whole time I lived in Arizona.

I've digressed; but these tangents are among the things I reflected on during this particular long outing on the road.

I felt great the whole race. At the turnaround I felt invincible, as though I'd barely started. I wore no watch (another thing of mine that's broken), so used the clock on my cell phone as a timer. When I checked my time at the turnaround, it said I'd done the outbound part in 4:17, just as the third runner was about to finish. I was sure I could finish in under nine hours, and maybe even grind out a negative split.

That didn't quite happen, but this time out I avoided the usual death march. My first sign of tiring came around twenty miles, the traditional location of the "wall." But I was well equipped with gels and the like, so I kept feeding myself, and my energy level revived. Unfortunately, I ran out of water, which didn't help. Normally I don't drink much (less than I should) in colder weather, and I just underestimated my needs, trying to cut back on weight carried.

Soon thereafter I stopped at the solar air compressor station in the wetlands just north of OSU, where bicyclists can get free air in their tires. I juggled some of my gear around, shed my full head cover and outer gloves, and stuffed them into my Camelbak, as it was the warmest part of the day and I was actually a bit too warm, which may have contributed to my slowing down. It got cooler later, but never uncomfortable since I worked hard to keep moving quickly as my decrepit body would allow.

When I got to the bridge that crosses the Olentangy River for the last time, which Google Maps tells me is 1.03 miles from the start/end, I started running without letup, and to my amazement, managed to run it all the way in. I rarely can do that. When I arrived there was just enough light left to see. I brought my headlamp, but obviously didn't want to make a stop to dig it out and put it on for the short bit that I would need it. Last year I could have used it, as I walked well over an hour in the dark.

My finishing time was 9:06. My 50K PR is 5:49, three hours and seventeen minutes faster, but that was ten years ago, and that was then and this is now. Given that I finished an hour and fifteen minutes faster than last year, only in part due to the extra mile or so that I traveled last year, and ended feeling strong, I'm pleased with the result, and confident that the hard work I've been doing lately to get back into shape has started to pay off.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

The Real Inventor of the Internet

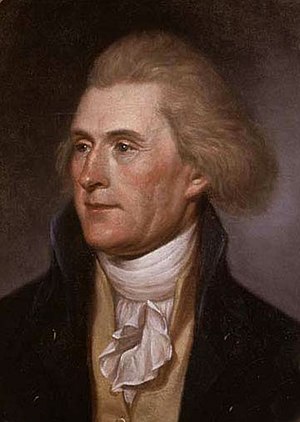

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaLess known than Gore's part is that played by none other than Thomas Jefferson, two hundred years before Mr. Gore.

By 1779, while the American Revolution was going full tilt, Thomas Jefferson, then a representative in Virginia's House of Delegates, submitted two proposals to the Virginia legislature. One was "A Bill for Establishing Cross Posts," intended to promote "the more general diffusion of public intelligence among the citizens of this commonwealth." He also introduced "A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge," with similar, but slightly different purposes. Implementation of either arrangement would require the state to invest in some infrastructure, at a time when funds among the states in the newly nascent nation were in severely limited supply.

General information, the type of communication that takes place between family, friends, and business people, could be handled by a well-designed postal system. But the purpose of cross posts was intended for the high-speed exchange of higher priority intelligence such as military data.

These plans were at first tabled by the Virginia Senate. Shortly afterward, by the end of 1779, Jefferson found himself unexpectedly elected governor. Discreetly, he refrained from using his greater authority to force adoption of his plan, reasoning that it had been the voted-on decision of the duly constituted legislature to reject the idea.

In 1780 the dynamics of the ongoing war changed. Communications between George Washington and Jefferson became unpredictable. Washington himself emphasized the value of establishing an efficient system of transmitting military intelligence as quickly as possible. As things were, it took over a month for decision makers to get word regarding the movement of soldiers, the outcomes of confrontations, and the needs for supplies. As a result, Jefferson's idea for establishing cross posts was revived and enacted.

Cross posts were mail route roads branching off the main north-south trunk road through Virginia, a sort of interstate highway of its day, connecting it with other American States. These roads created a flexible network, and constituted state-of-the-art communications technology.

Military intelligence was not to be carried by ordinary postal service. A special team of horses and riders were provided, along with a system of instructions for carriers, by means of which communiques were to be carried and handed off, with timed and dated receipts being required. These receipts were analyzed and used to predict delivery times with increasingly improved accuracy, or such was the theory.

Unfortunately for the war effort at that time, success of the system depended on couriers who were good at what they did, dedicated to the cause, and willing to shoulder their responsibilities seriously. Not all lived up to those standards, so the system didn't work as well as Jefferson had hoped. (Neither did a lot of things Jefferson thought up!)

Today the components that drive the modern Internet are well known. Messages are transmitted by means of data packets over networks of electronically connected devices such as routers, computers and cell phones, using a seven-layer stack of protocols. In Jefferson's day the same general objectives were accomplished by means of good roads, fast horses, and a system of rules for controlling the flow of messages.

Therefore, to anyone who cracks jokes regarding Al Gore's role in inventing the Internet, I will retort: No, it was really Thomas Jefferson who invented the Internet.

Tuesday, October 06, 2009

North Coast 24-Hour Endurance Run

The North Coast 24-Hour Endurance Run (NC24) in Cleveland, Ohio made a spectacular debut in its first edition on October 3–4, 2009. As host to the USA Track and Field/American Ultrarunning Association national championship, it drew a total of 107 runners: 82 men and 24 women. That the venue provides a fast course for racing is evident in that the race attracted many of the best runners in the US, and that 41 of those runners ended their day on the road with more than 100 miles, a figure that I personally regard as outstanding.

The race is so named because Edgewater Park, in which it was run, is on the edge of Lake Erie, with virtually the entire US Great Lakes system lying to the north, west, and east. The park features a looped walking path, USA Track and Field certified to be 0.90075 miles long, with an asphalt surface in perfect condition, and only one moderately tight turn, a concern to faster runners at times they are running at top speed, which in a 24-hour race is not often.

A primary concern in selecting a venue is to find one that lacks hills. It should be as flat as possible—ideally, as flat as a standard high school track. But this is rarely possible, except on actual tracks, which are sometimes available, but which presents other problems. Therefore, close is considered good enough.

The path at Edgewater Park is about as flat as any runner in an event of this type could hope for. All such courses tend to have a "better" direction for running, even though on a loop the cumulative rises and falls cancel each other out. NC24 was run in the clockwise direction. The start is by the ramada on the west end, next to a large parking lot, just off a sandy beach. There is s slight rise on the northwest corner, a slighter but longer one across the north segment, followed mostly by gradual descents, with one shorter but steeper drop in the southwest corner just before returning to the start.

Having had the privilege of participating in discussions with the race organizers for this race since the beginning, I'm aware of the great care that went into selecting the location. The day before the race, we arrived at Edgewater Park to take a look, when I also took a few photographs of the course, and also compared the lower park immediately to the west, which the organizers also considered using. While the lower course is prettier in some ways, with a much nicer ramada, the path has some difficult turns, snakes around too much, and even has one place where runners would have had to cross over a segment of grass. It was immediately apparent to me that the organizers made the right choice to use the other one.

How It All Came About

At the end of 2008, for various personal reasons, I nearly withdrew from ultrarunning entirely. I still walk long distances faithfully, and was able to average around fifty miles a week in training most of the summer, despite fighting off a problem with plantar fasciitis. The condition required aggressive treatment with two cortisone shots and a careful but quick return to longer distances, but without any running. It was when I started to add running back into the mix last June that the problem began. My goal in training was simply to get to the starting line feeling healthy and ready to go 24 hours continuously.

Despite my intent to focus on other pursuits, including my job, I became involved in discussions about presenting a 24-hour race way back in September, 2008. While out walking on my favorite training paths, exploring an area near where I live, but previously unknown to me, I discovered a little area that I thought would be nearly ideal for a 24-hour race. Though I still knew very few runners in Columbus, I did know a couple, and through a fortuitous and timely contact with Dan Fox, who lived then in Cleveland, I connected with some local runners and pitched the idea of creating a 24-hour race here. Though there was some interest, and a couple of other possible sites were suggested, there was not enough critical mass available to get the project rolling, particularly inasmuch as I was not willing to be the one to do all the work myself.

Word got back to Dan Fox through his friend, Columbus ultrarunner Rita Barnes, who attended my local discussion. It turned out that similar efforts were being proposed by some runners in Cleveland, including Dan Horvath, Joe Jurczyk, Connie Gardner, Debra Horn, and some others. Discussions were still in the larval stage. These are people who regret the loss of the 24-hour race at Olander Park in Sylvania, Ohio, near Toledo, about 125 miles west of Cleveland, which many US runners remember as being one of the best races of its kind, but which folded when the race director would no longer work on it.

One factor that influenced the effort to put on the race was the experience of Cleveland ultrarunning legend Connie Gardner, who came within forty meters of setting a new American 24-hour record last year at the Ultracentric race in Texas. As the story came to me, she quit from exhaustion after being told she had the record. Later, upon re-measuring the course, they found it to be short, denying her the record. That had to be a crushing disappointment to Connie, and I have no doubt it has haunted her ever since.

Before long, the informal chat that went on among the Cleveland runners became more focused. I was invited—may have invited myself—to continue participating in the discussions. I made it clear that I was unable to accept any responsibility as an organizer, but based on my years of working with Across the Years, might have some stories, observations, and suggestions gleaned from my experience that might be useful. And so it was that I came to be a peripheral participant in the planning for the race, never really doing anything myself other than shooting off my mouth, remaining appropriately neutral as an outsider about decisions made, but keeping myself informed about the progress.

Originally, I did not intend or expect to run the race myself, but as things developed, I saw that because it was within reasonably short driving distance (about two and a half hours), it might be practical to consider. At the time I was working at a highly stressful job, which had detracted significantly from almost all the other things I wanted and needed to do at the time, particularly from giving attention to matters of personal health and fitness. In fact, the situation was spiraling out of control. However, I no longer have that job (at this writing I'm unemployed), so at least I have had freedom to train more. The main questions were whether I could get back in shape adequate so as not to embarrass myself at a race, and whether we could budget it. Both of those factors worked out favorably, so I locked the event in my schedule and began to plan—just like the old days.

In the end, other than my performance at the race, everything went as smoothly as I could ever have hoped for, and we had a rewarding and refreshing three days of vacation away from the turmoil that constitutes our current life situation.

Preparations and Gear

Making preparations to leave seemed simpler than usual for this race. One possible reason is that now that I have spent 31 24-hour days looping around a track, I've learned to be self-sustaining during the race itself. I don't need and for the most part prefer not to have a crew, except I do appreciate it when Suzy is on site and will do me the occasional favor of refilling my water bottle or digging something out of my bag for me. But I would rather see her helping out the race as a volunteer than devoting exclusive effort just to me, because once I'm rolling, I don't need it.

Therefore, for this race I took a minimalistic approach. Some runners show up to these races with elaborate tents, crews, and shelves of equipment and special foods. From experience I know that I have no need of a tent for only 24 hours. So I determined that I would make do with a gym bag containing plenty of warm clothes in case it got wet or cold, a Craftsman hard plastic toolbox I use in which to put stuff like bottles of electrolyte, ginger, caffeine, lubricants, tape, scissors, and so forth, and a collapsible camping table and chair. This is, in fact, added up to far more than I had available at the FANS race in 2004, where all the gear I did have sitting in a gym bag on a chair got thoroughly soaked by a thunderstorm, and was not useful to me.

I've see some runners burn far too much time fussing around with shoe changes, re-taping, changing clothes, napping, and just about everything they can think of other than actually moving forward. I've made all those mistakes myself. At Across the Years last year, which was my last race, I went 72 hours without changing any clothing except outer layers of sweatshirts and coats, depending on the temperature. I tend to wear more than most runners because I get cold easily, but at that race I never even took off my shoes except to get in my sleeping bag. Yes, I stunk badly enough to be a candidate for burial at the end, but I'd saved a lot of trouble and time.

Therefore, even though I brought extra clothing to NC24, I dressed in the morning in what I intended to wear for the duration of the race, and that's exactly what I was still wearing at the end.

Travel

Suzy lined up a couple of errands she wanted to run to stores in the Cleveland area the day before the race, so we left home at 7:15 a.m. on Friday morning (October 2). We had been watching the weather forecast all week. It poured rain all day long, with a couple of brief respites late in the afternoon and evening.

Our first stop was at Edgewater Park, where I was able first to locate and padlock the two portapotties at Dan Horvath's request, and then walk the path slowly, taking photographs, including several that were off the course, from the nearby pier.

My first impressions were: the ramadas are funky; the whole park looks less than inviting on a soaking wet day; there are a few pretty views; the degree of rise and fall on the course would not be a problem for me, therefore even less so for any of the runners seeking to deliver superior performances; and the closeness to the lake is a pleasure to the eyes. I grew up four blocks from a beautiful beach on Lake Michigan, and also lived in Maine for a while, just a few yards from the Atlantic ocean, and love to see waterfront. We were also entertained by the presence of geese and gulls in abundance.

We headed next to where we would be staying, and returned in time for a pre-race meal at Porcelli's Bistro in downtown Cleveland. Far more runners showed up than were expected—I estimate about forty—requiring the restaurant personnel to hustle hard to take care of us, and taking a little longer than normal to get everything ordered and served. The staff did an outstanding job, and the food was delicious. They probably didn't make much money from alcohol from this group, but I'm sure they were happy to have the spike in business.

I had hoped to be in bed around 8:30. Even with the delay I was able to pull the covers up around my nose at exactly 9:35, had the alarm set for 5:35 a.m., and slept like a baby until 4:15, but continued to rest quietly until the alarm went off.

My morning preparations, which I now have down to a science, went quickly. We arrived at the park by 7:25, in time to find a choice location to set up my aid station, though in truth there is so much available space that there is room for every person participating to stake out a large and comfortable personal estate, with no limitations on size.

One of the greatest pleasures of any of these races, because the number of runners is small, so that in time you get to know a lot of them, is to meet new people—in this case, I especially enjoyed pre-race socialization with Stuart Kern from Maryland, and Columbus runners Kathy Wolf and Mike Keller, with whom I'd exchanged several rounds of email, but had never met in person. Also, I was at least able to touch palms with ultrarunning's current rock star Scott Jurek on his way in. We had exchanged email a few times in 2007 when he signed up to come to Across the Years, but he was unable to make the race, so we never met.

The Race Progresses

Following a brief pre-race informational meeting, the race began precisely at 9:00 a.m. as 107 runners set out on their journeys. The skies were gray and threatening most of the day, and it even sprinkled just a few drops barely a minute or two before the start—possibly our Creator's way of warning us that if we really want to do this, we're on our own. It never did rain during the race, and temperatures remained in the range of roughly 60 during the day to 50 at night. By about 8:30 p.m. the clouds even broke, and we were treated to the sight of this season's Harvest Moon, accompanied by an extraordinary shimmering glow. Whenever the moon was out, the light was bright enough to cast shadows. While a very few runners wore headlamps for night running, I can't imagine what they thought they needed them for, as between the moon and surrounding lights there was plenty of light to run by all night long.

The conversation between runners at every long distance race I have been a part of goes through a series of distinct phases:

Here We Go: Silly quips, mostly about how long the race is. "Are we almost done?" "Only 23:55 to go!" This lasts between one and five minutes, long enough for people to have to start breathing hard, and realize what they have gotten themselves into, when they would rather save their breath for something more intelligent.

Races We've Done: "So, I did Leanhorse two years ago." "Well I did Comrades this year." "That's great. I ran Hardrock." "I ran the Hardrock course in 1926." "And I ran Hardrock in 1925 while carrying a piano on my back." A little intimidating oneupmanship can sometimes be leveraged to a strategic advantage, even at this stage of the race.

The Strategy and Gear Phase: "How often do you plan to walk?" "Are you going to go straight through or sleep some?" "What are you drinking?" "Do you tape your feet?" "I think I may have forgotten to screw my head on right."

The Serious Phase: "Grunt." "Shut up and leave me alone." "Maybe if I just put my finger down my throat I'll feel better." (Been there, done that.)

The Reduced Expectations and Rationalizations Phase: "Well, I was really hoping to break Kouros' record, but short of that, I'll be happy just to stay out here a while and avoid getting injured."

The Late Night Phase: "Where's my Mommy???!!!"

The Race Phase: Except for the leaders, most people really have no idea where they are in the standings until sometime near the end, when they might take a look to see if there is someone nearby they can overtake, or someone just behind who is a threat. The last part of a fixed-time race, from about thirty minutes out, increasing in intensity until the very last second, is when the runners still on the course put forth their hardest effort, when little conversation takes place, because too much heavy breathing precludes it.

Lynn's Race

Lynn did not race. I lost count of my laps after four, and never had the slightest clue how far I'd gone or where I was in the standings, other than being certain it was way far down the list, until I got back to a computer after the race.

I've been working on a method of walking that looks a lot like slow running, the sort real old guys do, or runners who are completely depleted, except I do it when I'm fresh, and on purpose. It requires leaning forward, letting my arm swing determine the cadence, and just relaxing. Once in a while I start to slump over, like someone who is utterly exhausted, but if I remind myself: This is not running! This is walking!—I can take immediate steps to straighten up, relax, and concentrate only on my turnover and avoiding dragging my right foot, something I've always done, but can do less if I concentrate. Unfortunately, I don't have this technique down to where I can continue this motion hour after hour, but when I do it, I can sustain about a 14:00 walking pace, as contrasted with about a 17:00 pace if I just walk along normally. (And a lot slower later in the race.)

I've never had any kind of speed, but at times have been able to demonstrate fair endurance. My goal at the start of the race was to maintain forward motion, and not to take any breaks other than at the portapotty and whatever brief moments are necessary to stop at the aid station to pick something up, or at my table to grab my water bottle, take a couple of big gulps, and put it down again. In the past I have almost gotten through an entire 24-hour race without any sort of breaks—but not quite—and at three 100-mile trail races I got beyond 24 hours, once to 28 hours before having to drop, without needing to stop and sit except for rapid maintenance, and without extreme problems of sleepiness.

But at NC24 it was not to be. I felt perfectly fine for a long time, but by about twelve hours, I started to drag, and decided to take a caffeine tablet. When I use these in training (infrequently), they prove either to be a miracle drug, or they will have only marginal effect, and may irritate my stomach. At least I know that I was faithful about drinking, taking electrolyte, and eating, as I would grab something to eat almost every lap, making sure to get variety in my choices—fruit, pretzels, M&Ms, soup, sandwiches, pizza, macaroni and cheese, and cookies all come to mind as being on the menu for the day.

And so it was that at NC24 I went 14:30 without a single rest stop, but by the last lap before breaking, I was sure that if I tried to go another without a rest I would have taken a dive in the grass somewhere along the way.

I don't know what my problem was other than I've just lost too much of the fitness I once possessed, which wasn't exactly world class to begin with.

Reluctantly, I plopped myself in my chair, shut my eyes, and slept uncomfortably for a while. I brought no blanket or tent, so all I had to keep me warm was a large bath towel.

When I awoke, I promptly rolled to my left and experienced about five minutes of dry heaves. Fortunately, nothing came up. Strangely, this is sometimes the best thing that can happen to a person with an upset stomach. I felt much better after that, and got up to start walking again, but was still sleepy.

Two slow laps later I went down a second time, then walked two more laps and went down a third time, that time for quite a while.

After that I was all right once again, and continued on without further breaks until the end of the race. But this period of distress lasted the entire graveyard segment of the race, from 11:30 p.m. until 5:00 a.m.

From then until the end was just a matter of getting it done. I enjoyed watching other runners, particularly the leaders, who were running with such focus that I didn't dare to utter more than a word or two as they flew by. Sometimes I think I'd like to punch out the lights of the next person who says "Good job!" or "Looking good!" or the one I really hate: "Hang in there!" I got that last one less than two hours into the race. Did I already look like I was on my last legs and just needed to keep clinging for another twenty-two hours? I certainly didn't think so.

We were able to get credit for a final partial lap. White lines painted on the path were pre-certified as lying exactly in 100-yard increments from the start. At the end of the race a signal sounded, everyone still on the course stopped where they were, and threw down a stick they had been given about a half hour before the end with their number on it. Afterwards, a volunteer came by, picked up and recorded the sticks and gave credit up to the last 100-yard segment completed, tacking that total on to the number of laps run times 0.90075 miles.

I had misunderstood the segments to be a tenth of a mile. I ran rather than walking the last two or three minutes of the race. When I passed one marker with 30 seconds to go, thinking I could not get another tenth of a mile in 30 seconds, I pulled up and walked a bit more, but when the horn sounded I was not very far from the next mark, and realized that if I'd run it I could have made it past one more mark. That's when I realized they were not a tenth of a mile apart.

My total official mileage was 60.98045 miles, which I can comfortably round up to 61 miles for the purposes of conversation. If I had logged the extra 100 yards, most of which I did in fact actually run, it would have brought me to 61.03727 miles, which I would rather be able to round down so as not to be guilty of exaggerating my already meager accomplishment.

This figure constitutes a personal worst for me at 24 hours by a margin of 15.33 miles. Here is a list of my distances for all the 24-hour races I have run.

| Race | Date | Miles |

| Across the Years | 12/31/99 | 81.52 |

| Olander Park | 09/15/01 | 83.72 |

| FANS | 06/05/04 | 82.82 |

| San Francisco 24-Hour | 10/20/07 | 76.31 |

| North Coast 24-Hour | 10/03/09 | 60.98 |

Everybody Else

Although not everything went as expected during the race ("That's why they play the game," as Chris Behrman likes to say), there were some outstanding performances. Following are a few comments and anecdotes about various runners that I know, listed in finish order.

At the pre-race dinner we sat at the same table with Phil McCarthy from New York and five or six other people. Phil and the others talked about running; he sounded completely prepared. Should we call this listening session the McCarthy Hearings? Phil ran steadily the whole race, always alone, because no one else could run that fast, winning it and the national championship with 151.52 miles, along with a cash prize of $900.

John Geesler, from Johnsville, NY, is the Across the Years poster boy. We particularly like one shot from last year, when John stayed on the course despite being injured, and spent some time doing laps with Gavin Wrublik.

John has had some great days, and a couple of bad ones. His race at NC24 was superb, where he ran hard at the very end to come from behind and take second place by a tenth of a mile in the last lap, with a total of 139.41 miles.

Dan Rose, from Washington, DC, is the one John beat. Dan finished third with 139.28 miles.

For me the highlight of the race was watching Jill Perry from Manilus, NY run the best looking race I've personally witnessed, winning the women's race, championship, and prize money, with an outstanding 136.33 miles. Her running was smooth as glass the whole way. She told me after the race she had to take a break to tend to some physical problems, and also threw up once. Jill is a beautiful and shapely lady. Imagine my surprise when I learned she is also the mother of five children! Now I'm really impressed. A little research turned up that Jill has some sort of sponsorship deal with DryMax socks.

Cleveland area runner Debra Horn, who was on the 2009 U.S. Women's 24-Hour Run National Team, which won the silver medal at the World Championships, turned in a remarkable third place finish of 128.93 miles, behind Anna Piskorska of Blandon, PA, whom I did not get to meet.

John Geesler's friend David Putney, who did well at Across the Years in 2007, finished NC24 with 124.68 miles.

One of the great performances of the day was by Dave James. His 100-mile split was an almost unbelievable 13:06:52, but then he backed off and finished the race with 119.80 miles. His pace for 100 miles was 7:52.12. That's thirty seconds per mile faster for 100 consecutive miles than I have ever run any single mile in my whole life.

At times we could hear Dave coming up behind and requesting the inside lane, which I'm sure most runners were willing to yield. On one occasion, going around the sharp turn, where there is sand to the right and also a drop, he tried to squeeze by on my right, but since I don't wear my hearing aids when I run, I didn't hear him coming on that occasion. I'm not deaf—I just didn't realize he was nearly on top of me, and he almost wound up doing a head-first into the sand.

I guess the lessons we can learn from that experience is that the only proper way to pass, as on a highway, is on the outside, unless a runner is already well over to the left; and just because someone requests the left lane does not guarantee he will get it.

I mentioned Connie Gardner earlier, who also did a lot to help with creating the race. There was no opportunity for me to say hello to her beforehand. Once it started, Connie showed fierce concentration, and I didn't want to interrupt her focus, but after a few hours I happened to be just behind her when she was walking a few steps and regrouping, so I used that opportunity just to introduce myself. She looked at me with a look that said: "So what?" Bad timing. I said I knew she was obsessed at the moment and asked her how it was going. She said it was going all right, but I had seen that although she was running well by most people's standards, she seemed to me to be struggling. By the end of the race she had 116.20 miles—certainly not the record she had hoped for, but I admire Connie above all for not quitting just because she wasn't going to set a record.

In general, I tend to respect runners who show by their action that they recognize that in a fixed-time race there is no such thing as a DNF, and for better or worse, once you have logged one lap, you're in it until the end, and whatever your total is, that's how it will be shown in history. I imagine that for some runners that's harder to manage psychologically than a DNF.

I recognized Frederick Davis from Cleveland, because he ran the 72-hour race at Across the Years in 2002. When I said hello, his first words to me were, "You've put on some weight!" Busted. Frederick is about six feet and 140 pounds himself. He wanted to know if I'd been injured or just quit. It was helpful that he offered a menu of options. Right then wasn't a good time to expound on my life history and present circumstances, so I gave some weak excuse.

Ray Krolewicz from South Carolina may have run the most ultramarathons of anyone in the last thirty years, and he used to win an awful lot of them, too. He finished this one with 105.39 miles.

Dan Fox recently moved his photography business to Seattle. As one of the people who sparked the creation of this race, I'm glad he was able to return to run it. He ran most of the way with Rita Barnes, getting 101.79 miles, and Rita got 100.88 miles.

In fact, five runners got 100.88 miles indicating that all probably decided to go for 100 and quit. Good for them, but it seems to me if any had taken the trouble to run even a partial extra lap at the end, he would have bumped up his place in the standings by that many people. It is supposed to be a race, after all.

Don Winkley, who has run Across the Years numerous times, is one of the great runners of very long distances, including several finishes across the US and France, and a finish at the 205-mile Volunteer State trek across Tennessee last summer. Don is now 71, and finished NC24 less than half a mile under 100 miles. I saw him hauling butt at the end, too, so know he was going for it.

Leo Lightner, age 81, and from the Cleveland area, had an as yet unratified national age group record at 82.72 miles. Someone else set an age group record as well, but I didn't catch who it was.

Scott Jurek is ultrarunning's current rock star, and a legendary Nice Guy. He had an un-Jureklike day, quitting at 65.75 miles. As we were leaving I ran into him and encouraged him not to give up on doing a 24-hour race, since this is the third time that I know of where he has been entered but has not been able to perform up to his enviable potential. He laughed and said he wouldn't give up, but needed to do one when he wasn't tired. He ran another race not long ago (I forgot which one he said), and is still recovering from it.

Mark Godale, the current US record holder for 24 hours, came out of the chute like he was possessed. I learned later that he came not to run a full 24-hour race, but was shooting for a particular time at 100K in order to qualify for the National Team. I don't know what his goal was, but by 57.65 miles he realized he was not going to get it, so stopped for the day.

Technically, therefore, I beat Mark Godale in a 24-hour race! And with a little more effort that was probably within my power to produce, I might have been able to beat Scott Jurek as well, because that's how the game is played. In the end it's not about how fast you ran at the beginning before blowing up and melting down, but about how many miles you log in 24 hours. So I beat. Sorry. :-) (But they know that.)

This report would not be complete without mentioning that US National Team doctor Andy Lovy showed up with six of his medical students, leaving him freer to run himself than he usually is at Across the Years, where he is a fixture, and along with John Geesler (and me), is a 1000-mile jacket owner. Andy, who is now 74, got 38.73 miles.

And So ...

In January I thought my ultrarunning days were over. And maybe they are, but at least I managed to pull one more race experience out of the hat. When it was over I was a little stiff the rest of Sunday, but slept well and was able to spend seven hours on my feet visiting the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on Monday before driving back to Columbus. My plantar fasciitis did not flare up, and my blisters and other foot problems were so minor as to be insignificant.

There is something powerfully attractive about ultrarunning that draws me to it. With each race it remains to be seen whether I will ever do another, but I remain interested in the sport, so I suppose that as long as there are opportunities for me in it I will continue to return.

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Rubber Baby Buffer Dumpers

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaIt is not without reason that this blog has not been updated regularly for the last year. I apologize to all zero readers who have missed it.

Once a well-known author mused that the truly great authors, a group from which he excludes himself, seem unashamed about baring their souls. He said they write for God. So it is that I've had much on my mind of late, but have been reluctant to share it in a public place. I have been writing as much as ever—for God—but have been unwilling to publish.

Meanwhile, my mental buffers are as full as a hair-choked drain. How's that for a disturbing mixed metaphor? Now you know why I haven't been sharing stuff. It's time to dump just a few things so I can move on.

There have been changes to my once mundane but stable life. Persons who know me are aware that I moved from Phoenix, Arizona to Columbus, Ohio in mid-November, 2007. The overriding impetus that caused me to trade a happy life in my beloved Phoenix for Columbus was economic need; so I risked my future for one reason: to accept a promising job for which I had been recruited. The move was not the result of being driven by some irrational urge to live in Ohio, which thought had never crossed my mind.

Current economic conditions being what they are, that job lasted only sixteen months. As jobs go, while rewarding in some ways, and certainly challenging, in others it was a disappointment and not what I had hoped for. In my adult life I've held five primary jobs. In terms of satisfaction, benefits, and pleasure in doing, I cannot rate my most recent one as being among my top four favorites.

Nonetheless, here I am, still in Ohio. This in itself is not at all a bad thing. Ohio, and Columbus in particular, has rewarded me with experiences I would not have wanted to miss.

Inevitably, I'm impelled to make comparisons between life in Columbus and Phoenix, but have discerned that allowing the analysis to move me to conclude whether it has all been worth it is an exercise of little value to me or anyone else. Phoenix was then, Ohio is now and where my future will be, and there are good and bad points to both. Above all, it is my goal to remain where I am for the rest of my days in this life. Whether that is possible remains to be seen.

So hello to Columbus, with its river trails, Whetstone Park, Wexner Center, The Ohio State University, Franklin Park Conservatory, Bexley Library, Columbus Zoo, Germantown, Short North, and as yet untapped advantages. For better or worse, you now belong to me.

Saturday, September 19, 2009

Real Men Love Work

Author's Note: I wrote this piece in February 2002, but never got around to publishing it. It seems particularly appropriate in these times of economic crisis to do so now.

Some persons work for pleasure, others for money. It's a fact of today's life that most adults—men and women alike—must work outside their homes to earn money, whether they want to or not.

Some of what they take in pays for necessities such as food, clothing, housing, and transportation. If there is some left, a portion is put away for needs that are considered important, but not essential to immediate survival, such as education, or retirement. Inevitably, no matter how little a person makes, some portion goes for non-essential "frivolity": trips to the movies, dinner out, or a new video game for the kids.

Work itself is important, not merely the material benefits we recoup from doing it. Mankind is designed to carry on life in the context of an economy; in a Utopian sense we all work for each other's mutual benefit. To isolate oneself from human society, to live the life of the idle rich or the terminally lazy seems unnatural. Each of us is given a gift of life by our Creator, something none of us asked for. As soon as we are able, we are taught to be productive, to do things that ultimately benefit others, and that bring rewards in turn to the doer. In this way we all learn to validate the reason for our existence, proving ourselves worthy of the free gift.

Men, more so than women, tend to become preoccupied by their work outside the home. To many a man little is more important than the work he does for a living, regardless of whether he gets paid well for it, and in some cases, even if he is not getting paid at all. For such a man, his lifework becomes the mark of Who He Is, his legacy to be passed on to his family and posterity. It even becomes a label by which he is introduced to strangers: "This is Mr. Wiggenbottom, the CEO of Questionable Opportunities, Inc." "I'd like you to meet Dr. Wheezenhack, who is a history professor at Noaccount U." To be successful in work is considered by many to be successful in life, to be a successful man. To have the work taken away from a man is to have everything taken away: his identity, his purpose, and his life.

Many pursuits do not pay well. Aside from the need to make adequate provision for sustenance, making money is not the primary objective of many men. The idea is to make enough to allow one to continue doing the work he values.

Teachers who love to teach rarely do it for the money, because teachers usually make little—far less than good ones deserve. But they, like everyone else, have to make enough to live or find other jobs. Those who teach well speak of the satisfaction of influencing students for good. Others accept the lower pay because of the free time they have when school is out.

Most musicians I've known have found the satisfaction of making music sufficient all by itself. All they want is to continue doing it. If they can support themselves or even become rich without compromising their art, then all the better. But to become proficient in music requires time and effort, and these needs usually preclude the possibility of holding another job. If a musician skimps on this groundwork, he doesn't develop sufficiently to become an artist. Furthermore, playing musical instruments requires the development of extremely intricate motor skills, cultivated through constant, long practice from youth onward. If ignored for even a little while, these skills degenerate quickly, to the point they fall below a level that is useful for professional or artistic work.

Scientists, mathematicians, and creative artists become uncommonly absorbed by their work. Endless hours spent in deep intellectual isolation lead them to their keenest revelations, notions that may in turn be transformed into output: a theory, a proof, a drama, or a song. Such flashes rarely occur in a distracted state, or in a work span fraught with interruptions. Paul McCartney, one of the most publicly sought-after persons on the planet, said in an interview:

A form of work above all others is the self-sacrificing sort that is required to serve our Creator with a whole heart. Many of my closest associates openly declare that the work of teaching Scriptural truths to others is of such surpassing value, with the highest possible yield in personal satisfaction, that even family heads with a need to provide for others in addition to themselves willingly put it ahead of all other forms of work, in some cases accepting even menial jobs by which to make their livings, in order to make sufficient time to pursue spiritual goals.

Regardless of the sort of work that we engage in, whether by choice or out of necessity, it remains true that work itself is noble, and that there is no shame in any job that needs doing, no matter how lowly.

Some persons work for pleasure, others for money. It's a fact of today's life that most adults—men and women alike—must work outside their homes to earn money, whether they want to or not.

Some of what they take in pays for necessities such as food, clothing, housing, and transportation. If there is some left, a portion is put away for needs that are considered important, but not essential to immediate survival, such as education, or retirement. Inevitably, no matter how little a person makes, some portion goes for non-essential "frivolity": trips to the movies, dinner out, or a new video game for the kids.

Work itself is important, not merely the material benefits we recoup from doing it. Mankind is designed to carry on life in the context of an economy; in a Utopian sense we all work for each other's mutual benefit. To isolate oneself from human society, to live the life of the idle rich or the terminally lazy seems unnatural. Each of us is given a gift of life by our Creator, something none of us asked for. As soon as we are able, we are taught to be productive, to do things that ultimately benefit others, and that bring rewards in turn to the doer. In this way we all learn to validate the reason for our existence, proving ourselves worthy of the free gift.

Men, more so than women, tend to become preoccupied by their work outside the home. To many a man little is more important than the work he does for a living, regardless of whether he gets paid well for it, and in some cases, even if he is not getting paid at all. For such a man, his lifework becomes the mark of Who He Is, his legacy to be passed on to his family and posterity. It even becomes a label by which he is introduced to strangers: "This is Mr. Wiggenbottom, the CEO of Questionable Opportunities, Inc." "I'd like you to meet Dr. Wheezenhack, who is a history professor at Noaccount U." To be successful in work is considered by many to be successful in life, to be a successful man. To have the work taken away from a man is to have everything taken away: his identity, his purpose, and his life.

Many pursuits do not pay well. Aside from the need to make adequate provision for sustenance, making money is not the primary objective of many men. The idea is to make enough to allow one to continue doing the work he values.

Teachers who love to teach rarely do it for the money, because teachers usually make little—far less than good ones deserve. But they, like everyone else, have to make enough to live or find other jobs. Those who teach well speak of the satisfaction of influencing students for good. Others accept the lower pay because of the free time they have when school is out.

Most musicians I've known have found the satisfaction of making music sufficient all by itself. All they want is to continue doing it. If they can support themselves or even become rich without compromising their art, then all the better. But to become proficient in music requires time and effort, and these needs usually preclude the possibility of holding another job. If a musician skimps on this groundwork, he doesn't develop sufficiently to become an artist. Furthermore, playing musical instruments requires the development of extremely intricate motor skills, cultivated through constant, long practice from youth onward. If ignored for even a little while, these skills degenerate quickly, to the point they fall below a level that is useful for professional or artistic work.

Scientists, mathematicians, and creative artists become uncommonly absorbed by their work. Endless hours spent in deep intellectual isolation lead them to their keenest revelations, notions that may in turn be transformed into output: a theory, a proof, a drama, or a song. Such flashes rarely occur in a distracted state, or in a work span fraught with interruptions. Paul McCartney, one of the most publicly sought-after persons on the planet, said in an interview:

To be a songwriter, and to do my kind of work, you've got to be doing nothing. You've got to have a lot of time to yourself, which in most people's lingo is doing nothing. You're not working, you're not working out, you're just sort of sitting around. What a great job definition! Mine only requires a guitar and doing nothing. And I find that when I am doing nothing my favourite way of doing nothing is to make some music out of it. But you have to have some space for stuff to come into your brain. If you're sitting in the office all day thinking about business things it is not as conducive as having some time to yourself.Today, few people have the luxury of circumstances that Paul McCartney has to be able to do such work.

A form of work above all others is the self-sacrificing sort that is required to serve our Creator with a whole heart. Many of my closest associates openly declare that the work of teaching Scriptural truths to others is of such surpassing value, with the highest possible yield in personal satisfaction, that even family heads with a need to provide for others in addition to themselves willingly put it ahead of all other forms of work, in some cases accepting even menial jobs by which to make their livings, in order to make sufficient time to pursue spiritual goals.

Regardless of the sort of work that we engage in, whether by choice or out of necessity, it remains true that work itself is noble, and that there is no shame in any job that needs doing, no matter how lowly.

All that your hand finds to do, do with your very power, for there is no work nor devising nor knowledge nor wisdom in Sheol, the place to which you are going.—Ecclesiastes 9:10

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Life in Skool

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaNews from the Land of Educationville is not good. Children of parents who neglect to take a personal hand in the education of their progeny have little hope for any sort of meaningful future, and may as well resign themselves to being ignorant and stupid the rest of their lives. The tragic irony with ignorant people is that they don't know they are ignorant, so rarely do anything to improve.

In 1994 we had an experience with a different twist from what we've been hearing. My wife and daughter and I attended a preview orientation for sixth graders going into junior high school. On that night we all happened to be wearing dress clothes. I wore a business suit, and Suzy and Cyra-Lea wore dresses. To their credit, most others in attendance at least remembered to wear underwear, over fifty percent of them on the inside. Judging from appearances, we were the only persons present who knew all the letters of the alphabet and could count above ten—except for the principal, who was exceptionally cool. The day our son graduated from grade school we dropped by his office to leave him a gift to show our gratitude for putting up so patiently with our recalcitrant genius: a fifth of whiskey.

At the orientation the very first potentate, a very large man who was probably a football lineman in school, got up and immediately began speaking exuberantly about discipline, running down the list of sanctions against rule infractions: detentions for this, suspensions for that, expulsions for certain forms of miscreant behavior, executions by hanging for still others. People were taking notes and asking, "Excuse me, but was that two days of detention for throwing a sandwich at a teacher and three for dumping a soft drink on his head, or the other way around?" They didn't realize there would be no quiz at the end.

This was not what we had come to hear.

When the time for questions finally arrived, our daughter, who was eleven years old, broke the ice with the first query, saying: "This was all fascinating, but could you tell us a little about the educational programs and opportunities that exist for students at the school?" The principal, who knew her, was laughing his butt off in the background, while the friendly Gestapo just stared at her with his mouth open. He couldn't give her a straight answer, and we left without one, other than his assurance that if she was as good a girl as she seemed to be and worked hard she'd make out just fine. She was and she did and she did.

Saturday, September 05, 2009

Self Improvement

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaGiven that the publisher is McGraw-Hill, and that the original copyright is 1950, I should have anticipated that the quality of the contents might be somewhat better than one of today's functional counterparts, which might bear a title such as Thinking Clearly—For Dummies, and present anything but; but I was quite unprepared for what I encountered.

Far from being a compilation of naïve aphorisms bolsterd by lame observations, the book is actually an introductory text to the topic of general semantics (not to be confused with the related but different field of plain old semantics), and comes with an Appendix showing how to teach children the Tools for Thinking, another labeled "For Further Study," listing bibliographic references to fifteen fundamental source texts on the topic of general semantics, and an Index. For a good overview of the topic see The Institute of General Semantics Web site.

After reading through the book quickly, I immediately returned to the beginning and read it again, making marginal notes. The experience was life changing, as it opened my eyes to a whole field of study with which I was previously unfamiliar, and at the same time immediately served to make me more open-minded and objective in how I relate to other people.

The simple tools for thinking as outlined by Mr. Keyes may be summarized as follows, as paraphrased loosely from the first Appendix:

- So Far As I Know: Our knowledge of every matter, no matter how deep, is incomplete, and is subject to amplification that could change our viewpoint.

- Up to a Point: There are very few absolutes in this universe.

- To Me: However convinced we may be of the rightness of our viewpoint, it is ours alone; all others have their own as well.

- The What Index: No two objects are ever absolutely identical, though similarities exist.

- The When Index: The same object will be different at different times. Temporal context is important.

- The Where Index: Environmental factors change reality.

As happens with newfound interests, I wanted to know more, whereupon I set out to explore more advanced literature on the topic of general semantics as listed in the Appendix.

This led me first to People in Quandaries: The Semantics of Personal Adjustment by Wendell Johnson, a speech pathologist who was himself a lifetime severe stutterer. I still remember a paragraph in which Dr. Johnson substituted the nonsense word "blab" for every word in a paragraph of Nazi propaganda extolling the virtues of the Fatherland whose meaning was undefinable—sort of like text typically produced by business marketing departments today. All that was left was articles, prepositions, conjunctions and auxiliary verbs, so it came out looking like:

The blab blab of blab blab in the blab blab blab blab will blab blab blab blab blab blab and blab blab through blab and blab blab.

Following that I read Language in Thought and Action by Samuel Hayakawa, an English professor who taught general semantics, and who was for one term a U.S. Senator from California, a work that I found quite readable.

Thereafter I was led to check out from the library Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics by Alfred Korzybski, an exceedingly arcane presentation that is generally considered to be the original foundation text on the topic. It didn't take me long to give up on this one, as it required considerably more background in mathematics than I have to understand. By this time my attention was being drawn toward other topics. It was sufficient for me to learn that the field of general semantics had an origin, that the field is one of true science, and that all roads lead from Korzybski.

The effect of this research was to cause me from that time onward to listen more carefully and analytically to what others write or say.

For who has despised the day of small things?

—Zechariah 4:10

Life is just one damned thing after another.

—Elbert Hubbard

Related articles by Zemanta

- Nicholas Johnson/Wendell Johnson, The Communication Process (nicholasjohnson.org)

Monday, March 09, 2009

Mr. Sniff

My seventh grade assistant principal's name was Mr. Sniff. The man was as ludicrous as his name.

As an underling administrator, Mr. Sniff's primary duty was to render discipline to recalcitrant students, inevitably boys who wreaked havoc and disturbed the peace with activities like setting off cherry bombs in waste paper baskets and swearing at teachers, in a Father Knows Best era, when saying "hell" could get a child expelled and branded for life as a foulmouthed troublemaker.

Mr. Sniff was not kind, not good humored, not even pleasant looking. Students found endless riotous occasions to make sport of him because of his name.

One day Mr. Sniff was the faculty member assigned to monitor a library period. A plot, propagated in whispers around the room, was fomented that at precisely 2:03 p.m., everyone would make a loud SSSCHHHHNUFFF, which we were certain would evoke a good yuk from all persons present—perhaps even from Mr. Sniff himself.

Alas, this stunt went awry when the students got to giggling so much as the anticipated moment approached that the requisite silence beforehand needed to maximize the impact of the synchronized community snotsuck was disturbed. Ten seconds before the appointed time, Mr. Sniff stomped his foot, clapped his hands, and burst into scolding the class for being noisy, blah blah blah, heard it all before, yada yada yada. When the second hand hit straight up, the few who were not terrified by Mr. Sniff's rant, daring to snort despite it (including moi), were drowned out by his blustering phillipic. I'm sure he never heard it, being so wrapped up in the din of his own effusiveness. None of us got a chance to laugh about it, being under the gun.

Poor Mr. Sniff, who seemed about forty, but acted much older, met an untimely demise. During Christmas vacation that year he went to South America on vacation, where he rented a hotel room with sticky shutters. Upon putting his shoulder to them in order to heave them open, he went through the second floor window and fell to his death on the street below.

While the event in itself was inarguably a terrible and tragic episode (remember—the bell tolls for thee, yada yada yada), most of the students I knew had a hard time stifling a snicker when they first heard about it, because it seemed to be the sort of ending that was so much in character with the man that it might have been prophesied. To their credit, few of my peers were so disrespectful as to discuss it in flippant terms afterward, and he was soon forgotten.

Thereafter I made it a goal not to become the sort of person about whom, when I die, children will laugh.

As an underling administrator, Mr. Sniff's primary duty was to render discipline to recalcitrant students, inevitably boys who wreaked havoc and disturbed the peace with activities like setting off cherry bombs in waste paper baskets and swearing at teachers, in a Father Knows Best era, when saying "hell" could get a child expelled and branded for life as a foulmouthed troublemaker.

Mr. Sniff was not kind, not good humored, not even pleasant looking. Students found endless riotous occasions to make sport of him because of his name.

One day Mr. Sniff was the faculty member assigned to monitor a library period. A plot, propagated in whispers around the room, was fomented that at precisely 2:03 p.m., everyone would make a loud SSSCHHHHNUFFF, which we were certain would evoke a good yuk from all persons present—perhaps even from Mr. Sniff himself.

Alas, this stunt went awry when the students got to giggling so much as the anticipated moment approached that the requisite silence beforehand needed to maximize the impact of the synchronized community snotsuck was disturbed. Ten seconds before the appointed time, Mr. Sniff stomped his foot, clapped his hands, and burst into scolding the class for being noisy, blah blah blah, heard it all before, yada yada yada. When the second hand hit straight up, the few who were not terrified by Mr. Sniff's rant, daring to snort despite it (including moi), were drowned out by his blustering phillipic. I'm sure he never heard it, being so wrapped up in the din of his own effusiveness. None of us got a chance to laugh about it, being under the gun.

Poor Mr. Sniff, who seemed about forty, but acted much older, met an untimely demise. During Christmas vacation that year he went to South America on vacation, where he rented a hotel room with sticky shutters. Upon putting his shoulder to them in order to heave them open, he went through the second floor window and fell to his death on the street below.

While the event in itself was inarguably a terrible and tragic episode (remember—the bell tolls for thee, yada yada yada), most of the students I knew had a hard time stifling a snicker when they first heard about it, because it seemed to be the sort of ending that was so much in character with the man that it might have been prophesied. To their credit, few of my peers were so disrespectful as to discuss it in flippant terms afterward, and he was soon forgotten.

Thereafter I made it a goal not to become the sort of person about whom, when I die, children will laugh.

Sunday, January 11, 2009

Elliott Carter at One Hundred

On December 8, 2008 Elliott Carter celebrated his one-hundredth birthday, in good health and spirits. He still works several hours and goes for walks daily.

This milestone was observed along with a flurry of accolades and honorary concerts, including a world premiere in New York performed by Daniel Barenboim and James Levine, both Carter champions from the musical establishment. Amidst the celebrations, Carter performances are given standing ovations, but for decades most people have found Carter's uncompromisingly modern music baffling, and most flat out dislike it. Carter himself does not care, and is unwaveringly dedicated to writing the music he believes in and hears. In an interview with Carter, Levine and Barenboim, given the day before the big occasion, Carter expressed his longing to get back home soon to the apartment in Greenwich Village he has lived in since the forties, so he could get back to work on his latest composition project. I'm certain that his dedication to a regular routine, and leading a fairly simple live, despite being wealthy since birth, have contributed to his longevity.

Being a Carter fan is sort of like being a Cubs fan. It's fashionable to love the Cubbies if you're from somewhere else and hop on the bandwagon when they're doing well. But if you've been following the team's travails since 1948 and even lived in Chicago for a long time back then like I did, you can lay a legitimate claim to being a fan.

Similarly, if you bought the Walden Quartet recording of Carter's monumental first String Quartet, listened to it a couple hundred times, often with the score, knew and were even friends with members of the Walden Quartet, have a record and CD collection glutted with Carter recordings, have even had a composition lesson with the great man himself, and have been a relentless admirer since about 1958—like me—then you can lay a legitimate claim to being a Carter fan.

Soon Mr. Carter will slide into relative obscurity again, and doubtless will die not too long afterward, as he can't have much time left actuarially speaking, while most new converts who have recently started listening to Elliott Carter's music will realize it ain't easy sledding, will slow down, and then stop, or go back to the mind-numbing execrations of Phillip Glass, and will eventually return to hating Carter's music again.

Color me cynical.

This milestone was observed along with a flurry of accolades and honorary concerts, including a world premiere in New York performed by Daniel Barenboim and James Levine, both Carter champions from the musical establishment. Amidst the celebrations, Carter performances are given standing ovations, but for decades most people have found Carter's uncompromisingly modern music baffling, and most flat out dislike it. Carter himself does not care, and is unwaveringly dedicated to writing the music he believes in and hears. In an interview with Carter, Levine and Barenboim, given the day before the big occasion, Carter expressed his longing to get back home soon to the apartment in Greenwich Village he has lived in since the forties, so he could get back to work on his latest composition project. I'm certain that his dedication to a regular routine, and leading a fairly simple live, despite being wealthy since birth, have contributed to his longevity.

Being a Carter fan is sort of like being a Cubs fan. It's fashionable to love the Cubbies if you're from somewhere else and hop on the bandwagon when they're doing well. But if you've been following the team's travails since 1948 and even lived in Chicago for a long time back then like I did, you can lay a legitimate claim to being a fan.